- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images. Essays by Richard Armstrong, Stephanie Barron, Roberta Bernstein, Sara Cochran, Michel Draguet, Thierry de Duve, Pepe Karmel, Theresa Papanikolas, Noëllie Roussel, Dickran Tashjian, Lynn Zelevansky. Ghent and Los Angeles: Ludion and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2006. 256 pp; 250 color ills.; 50 b/w ills. $60.00 (cloth) (9055446211)

The impetus behind the exhibition Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is the presence in the permanent collection of an iconic modernist painting, The Treachery of Images (1929), better known by its painted inscription, Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This Is Not a Pipe). The concept had several things going for it. These days, museums are looking for ways to utilize their collections to create special exhibitions, the better to retain audiences attracted to these expensive enterprises. LACMA’s enigmatic Magritte, known and loved by a broad swath of the museum-going and potential-museum-going public, promised to be a rewarding focus for such an effort. In addition to its popularity, The Treachery of Images, which exists in a number of versions and variations, also happens to be a work of art that has had an incalculable impact upon artists in a myriad of ways sure to be of interest to artists and art historians.

The exhibition was created by LACMA’s senior curator of modern art, Stephanie Barron, with Michel Draguet, director of the Musées Royaux des Beaux Arts de Belgique, and Sara Cochran, assistant curator of modern art at LACMA. What they have accomplished by bringing together over sixty works by Magritte displayed alongside an equivalent number of works by thirty postwar and later artists in an installation designed by Los Angeles artist John Baldessari is to let us see Magritte through the eyes of his fellow artists. This proactive perspective proves to be infinitely more interesting than the typical “influence of . . . in the art of . . .” approach that comes most easily to art historians—for example, in the concurrent Whitney exhibition, Picasso and American Art, which has received largely negative reviews for its reductionist approach. (I have not seen it.) LACMA’s attitude, in contrast, is expansive, and salted with fresh insight into both Magritte and artists whose work riffs on his.

The inspired intelligence of this series of moves (it was LACMA’s new director, Michael Goven, who suggested binging in Baldessari) is clear upon entering the show. I knew in advance about the blue carpet with its Magritte-like pattern of white puffy clouds and the ceiling wallpapered with aerial views of LA freeways, and wondered how the art could be anything but overwhelmed within this environment of visual trickery. Entering the exhibition, however, I found myself occupying a zone of giddy euphoria quite different from LACMA’s typical gray-carpeted, white-walled special exhibition spaces. Evoking infinity and flux, Baldessari’s galleries prove surprisingly hospitable to Magritte’s own aesthetic of—to use his favorite word—“mystery.”

My fellow visitors seemed to share this mood, darting from one work to another, talking animatedly with each other and with the guards, whom Baldessari had dressed in black topped off with Magritte’s signature bowler hat. The guards may have been a bit warm in this dignified getup (I spotted one of them fanning herself with her hat), but they looked great, and seemed to be loving the attention. Visitors are not allowed to photograph the paintings, but they can photograph the guards and their friends with the guards, favorite paintings hovering discreetly in the background.

The labels are a mixed affair. On the plus side, their contents are for the most part to the point, and text labels for the various sections are placed nearer the exits than the entrances to individual galleries. So rather than didactic guidelines for how to think about what they are about to see, visitors encounter opportunities to reflect on what they have just seen. It made me wonder why no curator to my knowledge has done it quite this way before.

On the negative side: though English translations of Magritte’s French are provided for many of the short phrases in the paintings, this is not the case for his longer, more discursive texts—so useful for understanding what Magritte was up to. Given the absence of English translation, it would have been helpful to display the five sheets of Magritte’s 1928 Words and Images in close enough proximity to the brochure for the 1954 Sidney Janis exhibition, Magritte: Word vs. Image, where Magritte’s homilies are translated, to allow viewers an understanding of what Magritte’s word/image relationships are actually about. The next day, as it happened, I saw at the Getty Research Institute a terrific model for how to display foreign-language material. In the exhibition A Tumultuous Assembly: Visual Poems of the Italian Futurists (August 1, 2006–January 7, 2007), Italian concrete poetry was accompanied by English facsimiles in a way that added quite a lot to viewer comprehension.

As Stephanie Barron points out in her introductory essay for the catalogue, Magritte’s puzzling oeuvre comes most clear within the context of work by other artists. For example, she quotes a review of MoMA’s 1966 Magritte retrospective in which critic Max Kozloff wrote that, seen within the context of Johns and Pop art, “Magritte seemed more profound and liberating than before” (10). For this viewer, the artistic éminence grise of the exhibition was Marcel Duchamp, who performed Baldessari-like artistic interventions on exhibitions he was associated with—for example the doilies with which he surrounded the frames in the first exhibition of the Société Anonyme, Inc. in 1920, and the famous “mile” of crisscrossed string that blocked access to the works in the 1942 exhibition, First Papers of Surrealism.

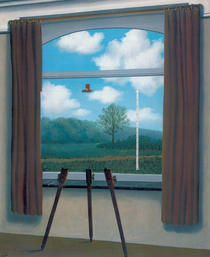

Magritte is how Duchamp might have turned out, had the older artist not decided early on to give up on painting as his primary artistic medium. (His “last” painting, Tu m’ of 1918, contains a Magritte-like pointing hand.) Like Duchamp, Magritte was concerned with the nature of reality and the omnipresence of “mystery” behind ordinary appearances. Neither of them thought much of psychology. Magritte professed disdain for the impact of the past, commenting about another iconic picture, La condition humaine (1933), which shows a landscape on an easel before a winow hiding the landscape presumably framed by the window:

This is how we see the world—we see it outside ourselves, and yet the only representation we have of it is inside us. In the same way, we tend to situate within our past something that is happening in the present. [In the situation depicted in La condition humaine] time and space lose the crude meaning which is the only one they have in everyday experience.

C’est ainsi que nous voyons le monde. Nous le voyons à l’extérieur de nous mêmes et cependant nous n’en avons qu’une representation en nous. De la même maniére, nous situons parfois dans le passé une chose qui se passé au present. Le temps et l’espace perdent alors ce sense grossier dont l’expérience quotidienne es seule à tenir compte. (From “La ligne de vie II,” in René Magritte, Écrits complets, A. Blavier, ed., Paris: Flammarion, 1979, 144.)

Magritte’s comment suggests that The Treachery of Images (This Is Not a Pipe), from four years earlier, may not be just about the nature of representation, but about the nature of relationship, of which representation is just one, very interesting (to artists anyway), category. A related drawing, Pipe-bite (1943, not in the exhibition), where the stem of the pipe becomes an erect penis, supports this notion, which Barron touches upon in her discussion of the 1936 painting, The Philosopher’s Lamp (16).

Magritte never did give up on painting (although he was scheduled to cast some sculptures just before he died). On the contrary, after moving variously through deadpan-realist, faux-Impressionist, and vache (“ugly”) modes of paint-handling, Magritte adapted in his late works to hallucinatory effect a Leonardo-like aerial perspective. Unlike Duchamp, who was in so many ways a more liberated artist, Magritte clung tenaciously to the realm of the visible. This fact may account for the heavy impact of this essentially conceptual artist within the realm of the visual arts. His work may even have influenced Duchamp’s own late-life, startlingly realistic icons, like the fly-covered sole of the artist’s bare foot in the haunting relief, Torture-morte, from 1959.

I bring in Duchamp by way of comment, not complaint. Magritte and Contemporary Art might have been a different show, but not a much better one. The choice of artists is first-rate, from Marcel Broodthaers, who is quoted in the catalogue as claiming, “it was with this pipe that my adventure began” (95); to Jasper Johns, whose flagstones and reverberating patterns suddenly made sense to me in a way they had not before; to Ed Ruscha’s own powerful pairings of word and image; to Vija Celmins—those burning houses, yes!; to Robert Gober, of course, and others, including Baldessari himself. The occasional misses, like Barbara Kruger, are rare, and more than offset by numerous perceptive hits.

As for the catalogue, although it contains a number of interesting and informative short essays and artist interviews and is beautifully produced, I miss any thoroughgoing treatment of Magritte’s imagery like those by W. Van den Bussche and Christine Vuegen in the miserably translated René Magritte and the [sic] Contemporary Art, produced by the Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Oostende. But then, that 1998 exhibition contained not a single actual work by Magritte, so the catalogue had to do it all. LACMA’s exhibition is beautifully balanced between Magritte and artists inspired by Magritte. For the catalogue, the organizers chose to emphasize his influence, which makes a certain sense.

“Art,” Magritte wrote his friend Harry Torczyner five years before he died in 1967, “evokes the mystery without which the world would not exist, namely, the mystery that must not be mistaken for some kind of problem, difficult as that problem may be. I take care to paint only images that evoke the world’s mystery. In order to do so, I have to be very wide awake” (Harry Torczyner, “L’Ami Magritte,” Correspondance et Souvenirs. Antwerp: Fonds Mercator, 1992, 15). It is, finally, Magritte’s adroit deployment of painterly realism to get behind the appearances of things, his evocation of mystery with eyes wide open, that continues to attract artists and audiences alike. Rarely has the profound lightness of Magritte’s art been better served than by Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images.

Jacquelynn Baas

Director Emeritus, University of California Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive