- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

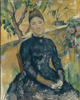

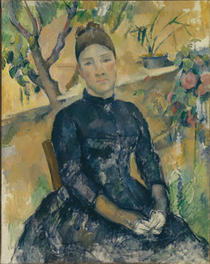

Madame Cézanne was an unprecedented, likely once-in-a-lifetime exhibition that spotlighted Paul Cézanne’s portraits of his wife, Hortense Fiquet. Organized by Dita Amory, Acting Associate Curator in Charge and Administrator of the Robert Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the show sought to revise misconceptions, especially about the artist’s affection, or lack thereof, for his wife, and reinvigorate general and scholarly interest in this group of work. To that end, it presented twenty-four of the twenty-nine known portraits of Hortense and contextualized them with less formal graphite sketches, watercolors, and one of her few extant letters. In addition, an adjacent gallery displayed a complementary selection of Cezanne’s works on paper from the Met’s collection, exemplifying the artist’s approach to other subjects, including the bucolic trio: apples, bathers, and trees.

Neither the exhibition nor the catalogue radically departed from prior interpretations. However, facts about Hortense’s life helped to correct inaccuracies about her character and relationship with her artist-husband, and analyses of Cézanne’s painting and drawing techniques elaborated the details of his artistic production, from the specific materials he used to the stages of his compositional development. In lieu of offering groundbreaking insights, the show provided an assessment of the “state of the field” and furthered the thesis about the complex emotional interrelationship between artist-husband and model-wife advanced by others. It is notable that no academic art historians contributed to the exhibition catalogue, which would have been enriched with their participation.

The exhibition, installed in the upper level of the Robert Lehman Wing, began with eighteen oil portraits, hung along two diagonal walls at the far end of the diamond-shaped corridor. This arrangement meant that the show lacked a single, predetermined starting point. Depending on which side visitors entered the Robert Lehman Wing, they might first encounter an early, Corot-like painting, Madame Cézanne Leaning on a Table (ca. 1873–74), or the more canonical and monumental Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair (ca. 1877), which inspired Henri Matisse’s Woman in Blue (1937). The open and fluid character of the installation partially fulfilled one of the goals of the exhibition: to enable comparisons among the artworks. Viewers could survey groupings of portraits—ten on the left; eight on the right—but they could not see all of them in a single glance due to the chevron-shaped architecture.

On both walls, the works were organized roughly chronologically and in formal terms by the similarity in Hortense’s dress, which varied from light phthalo to dark ultramarine blue and from plain to patterned with stripes or spirals. This method of organization continued in the low-lit gallery adjacent to the corridor: four portraits of Madame Cézanne in a red dress, united for the first time since they left the artist’s studio, appeared along the far wall framed on either side by intimate graphite sketches and watercolors, showing Hortense at rest, sleeping, reading, or sewing, as well as two unfinished oil portraits. Opposite the four portraits was a vitrine, containing archival materials: a copy of the dealer Ambroise Vollards’s 1914 monograph on Cézanne, which reproduces on its frontispiece a sketch of Hortense sewing, the original of which was on display across the room; three intact sketchbooks; and an 1890 letter from Hortense to her friend Marie Choquet, adding her “voice” to the exhibition. Beside the glass case, a digital display of rotating sketchbook images rested on a pedestal.

This assemblage of portraits and sketches of Hortense reinforced visually much of what already has been said about them by art historians such as Ruth Butler, John Rewald, and Susan Sidlauskas, and by the artist’s biographer Alex Danchev: the sketches have a softer, more sensual, and alive character than the oils; and the paintings lack consistency in the representation of their sitter—not only does her appearance change subtly and sometimes dramatically, but also her emotional state alters. For example, the juxtaposition of two images of her wearing a wide-striped dress reveals a shift from a seemingly inscrutable downward gaze in the earlier depiction from around 1877 to a more melancholic look with tilted head and downturned lips from 1890–92. In the later painting, weighty stripes underscore her sense of sadness, effectively dragging the beholder’s eyes down, thereby mirroring her mood. Other pairings focus on alterations in form, such as the exposing or obscuring of the spiral pattern running along the edges of her blouse or the teardrop drapery behind her. Such details certainly seem less connected to the expression of any emotional state than to the internal unity of the painting itself.

Although not particularly revelatory, the installation drew on current and more conventional methods of display as though echoing Cézanne’s own combinatory—modern and traditional—approach to art, elaborated in the catalogue essays about his painting and drawing techniques by Charlotte Hale and Marjorie Shelley, respectively. While the fluid layout that allowed visitors to select their path suggests more recent open-ended and participatory approaches to exhibition design, the chronological arrangement largely driven by progression in time and formal concerns harkened back to more conservative arrangements. Likewise, sketchbook pages were displayed with the aid of relatively new technology, but without the now ubiquitous touch screen.

The most significant problem with the installation was the gallery space itself, especially the corridor area, whose masonry and glass architecture created an airy and grand atmosphere that recalls that of a skylit hotel or office-building lobby from the early 1970s. The impersonal and overwhelming quality of this space, designed by Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo in 1975, exacerbated the sense of coldness and detachment frequently associated with Cézanne’s depiction of Hortense. Consequently, the presentation dehumanized the portraits, contradicting the exhibition’s attempt to humanize Hortense by baring biographical details. Besides undermining part of the show’s thesis, the presentation, I would argue, compromised the intended effect of the paintings, which counter traditional portraiture in their lack of emphasis on mimetic depiction and psychological exploration. The radicality of Cézanne’s approach is lessened when the portraits appear in a setting that competes with and even heightens their aloof quality. Instead, they should be displayed in a more intimate space—the sort of interior for which they were intended and the type of setting that would cause them to stand out by contrast.

Like the exhibition, the accompanying catalogue relied on biography and artistic process, missing opportunities for broader art-historical and contextual analysis. It consisted of seven essays by curators (Amory, with the assistance of Kathryn Kremnitzer, and Ann Dumas), conservators (Hale and Shelley), a biographer and journalist (Hilary Spurling), and the great-grandson of the artist and his wife (Philippe Cézanne). The catalogue explored the portraits, their chronology, and their reception; Hortense’s biography; the artist’s art supplies and his drawing and painting techniques; a comparison of Cézanne’s and Matisse’s portrayals of their wives; and the impact of Cézanne’s depictions of Hortense on his contemporaries and followers, from Paul Gauguin in the 1890s to Elizabeth Murray in the 1970s. Of scholarly interest may be the compilation of provenance, exhibition history, and bibliography for each known portrait, drawing, and watercolor of Hortense. In the essays by Amory, Philippe Cézanne, and Dumas, editing and more coordination among authors could have reduced the repeated references to Hortense’s life story, especially the dispelling of rumors about her lack of appreciation for her husband’s art and her failure to visit her husband’s deathbed. Moreover, Dumas’s essay, “The Portraits of Madame Cézanne: Changing Perspectives,” concludes in an unsatisfying way: after a detailed survey of the literature on these paintings, from the early response of the poet Rainer Maria Rilke to recent art-historical interpretations by Butler, Tamar Garb, and Sidlauskas, she writes: “In the end, perhaps the portraits of Hortense elude analysis. They are works that are essentially private, experimental, and open-ended” (105). On the whole, the catalogue seems historically imbalanced. It follows the recent tendency of attempting to make historical art relevant by exploring its legacy at the expense of situating it in relation to its antecedents.

The exhibition and its catalogue would have been more successful if the curators and essayists had taken advantage of the encyclopedic collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. To locate Cézanne’s works in a broader history of art, the curation could have directed visitors to portraits in other galleries, perhaps including this information on a wall panel near the one detailing the results of recent conservation on the Met’s Madame Cezanne in the Conservatory (1891). Although the exhibition missed an opportunity to present Cézanne’s portraits of Hortense in their historical and intellectual context, it did offer a rare opportunity to see almost all of them together and to scrutinize this discrete subject in the artist’s oeuvre. It underscored for me that the drama and intrigue in Cézanne’s post-1870s work lies more in the painted surfaces of his images than in his subjects and their gestures.

Isabel L. Taube

Lecturer, Department of Art History, Rutgers University