- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Farewell to Surrealism: The Dyn Circle in Mexico at the Getty Research Institute aptly starts with an enlarged photograph of Wolfgan Paalen holding a recently painted portrait of André Breton. Standing in front of, but not at all blocking Breton’s enormous painted visage, Paalen stares expressionless at the camera. As the photograph intimates, Breton loomed large over Paalen’s artistic practice and his new community in Mexico, which he named the Dyn group, meaning Greek for “the possible.” Even though Paalen announced his farewell to Surrealism and to the tight strictures of Bretonian Surrealism in particular, it seems that he could not really shake Breton or the Surrealist strategies that he proselytized. According to Gordon Onslow Ford, a member of the Dyn group, “Dyn was a continuation of surrealism with a modified point of view” (as quoted in the exhibition catalogue, 5).

En route to Mexico, Paalen, his wife—the writer and occasional painter Alice Rahon—and their companion, the photographer Eva Sulzer, stopped in the Pacific Northwest to view totem poles and the Canadian landscape (a short film of what they saw in British Columbia is included in the exhibition). Along with the Pre-Columbian artifacts the group would encounter in Mexico, the totem poles and vistas in Canada were a continued source of inspiration. Several of Sulzer’s photographs taken while in Canada are included in the exhibition. After two years in Mexico, Paalen announced his move away from Breton and Surrealism in the pages of his newly founded periodical, entitled Dyn. Though short-lived (only five issues were published in all), each functioned as a showcase for Paalen’s ideas concerning art, science, anthropology, and archaeology. (At first, the circulation of Dyn was quite limited. Only sixty copies of the initial issue were printed—distributed by Gotham Book Mart in New York—in English and in French.) Each issue is on display in the exhibition.

In Mexico, Paalen, Rahon, Sulzer, Onslow Ford, and Edward Renouf became entranced by the Pre-Columbian art and architecture that they had seen first in the pages of the Surrealism-affiliated journals Minotaure and Documents, and perhaps even in the Trocadero in Paris. Also important were the new relationships made with Latin American artists living in Mexico City, many of whom were featured in the pages of Dyn. Several of these artists, including Carlos Mérida, Miguel Covarrubias, Rosa Rolando, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, and César Moro, all feature prominently in the exhibition.

Paintings act as anchors within the opening gallery. Placed below each painting is a large case filled with issues of Dyn, along with drawings, photographs, and, perhaps not surprisingly, carefully selected issues of Minotaure. Preceded by paintings by Rahon and Onslow Ford, Mérida’s All in Rose (1943) is hung above a case containing the second issue of Dyn opened to a drawing by Mérida and a poem by Moro, and the sixth issue, which includes a color reproduction of All in Rose. Side-by-side with the second and sixth issues of Dyn are a photograph of Pre-Columbian clay figurines and a drawing of a claw from a Chilkat blanket, both by Covarrubias. The relationship made between these objects and Mérida’s painting is purposeful as it connects the imagery in Mérida’s canvas to the Pre-Columbian examples so accurately copied and photographed by Covarrubias. It is unclear, however, whether Mérida was familiar with the actual objects represented by Covarrubias, as this is not mentioned in the didactic material. It nevertheless points to an interest in Pre-Columbian forms by Latin American artists like Mérida at this particular moment in time.

What is certain, and fascinating in my opinion, is that the international public encountering Covarrubias’s representations of recent anthropological finds in the pages of Dyn saw illustrated representations of these objects, not photographs. The detail and care that Covarrubias took to transcribe these objects onto the page is made all the more evident in a grouping within the exhibition entitled “Ethnography and Indigenismo” wherein Covarrubias’s illustrations from Dyn nos. 4 and 5 are on display. Dyn circulated within Mexico, as well as in the United States and England. Covarrubias’s drawings, photographs, and the account of his excavation at Tlatilco, therefore, introduced subscribers to the anthropological fieldwork taking place in Mexico. Alongside Covarrubias’s detailed accounts of anthropological digs, these objects were given historical specificity and context in the pages of Dyn.

Mérida incorporated Pre-Columbian motifs, amorphous and ambiguous figures, and geometric shapes in All in Rose; however, the painting is also evidence of the inspiration he drew from new developments in modern art. In Dyn no. 6, Mérida’s painting is not paired with Covarrubias’s illustrations as it is in the exhibition; rather, his painting is used as one of several illustrations in the final pages of “The Modern Painter’s World” written by Robert Motherwell (Robert Motherwell, “The Modern Painter’s World,” Dyn 6 [November 1944]: 9–14). The final issue of Dyn (no. 6)—which has scant presence in the exhibition—features texts by Motherwell and Paalen on modern painting alongside a bevy of illustrations by artists associated with Dyn and those working elsewhere, such as Henry Moore and Jackson Pollock. This issue emphasizes the similarities between modern artists in even the most distant locales, putting these artists and authors into dialogue. It is a shame that the exhibition does not include more from this pivotal issue, as it demonstrates the surprising possibilities for exchange that Paalen’s journal fostered. In part, this may be due to the specific argument for the centrality of Mexico that the exhibition intends to make; yet with a glossing over of the international exchanges that occurred between artists in Mexico, the United States, England, and Europe, a particularly poignant thread is left relatively unmined.

However, by doing so, the exhibition enables viewers to recognize more fully the impact that Pre-Columbian objects from the past had on Dyn artists. In The Marriage (1944) by Onslow Ford, for example, the influence of Pre-Columbian patterns and motifs is quite pronounced. The painting’s dynamic composition of lines appears almost identical to that in a reproduction of a color photograph of a ceramic vessel from Capacha, Colima, Mexico, placed in the wall case beneath it. However, after examining Minotaure nos. 12–13 (also on display in the wall case), in which an early painting by Onslow Ford is reproduced, it becomes clear that the artist’s practice already included the kinds of radiant lines found in the Capacha vessel, which begs the question—what kind of impact did his new locale truly make on Ford’s practice? Was it an altogether different experience seeing Pre-Columbian sculptures as reproductions in Minotaure, Documents, or in person at the Trocadero than it would have been to view them at a market in Mexico? These suppositions are difficult to assess, but luckily the exhibition allows viewers to ask these kinds of questions of the objects on display.

The presence of various issues of Minotaure throughout the exhibition somewhat undermines the argument that the move to Mexico freed Paalen from the constrictions of Bretonian Surrealism. This is evident in the photographs by Sulzer that form the finale of the exhibition. Sulzer co-financed Dyn; therefore, it is perhaps not astounding that her photographs would appear within its pages. Yet Sulzer’s work (a collection of which was recently acquired by the Getty, and consists of 122 photographs and 3 small booklets) is completely in sync with the kind of Surrealist landscape photographs that appeared in the pages Dyn. These sublime photographs are absent of people, appearing timeless and otherworldly. Though indebted to Surrealist strategies, Sulzer’s photographs are an attempt to adequately capture the new, strange, and tantalizing landscapes and objects she encountered in Canada and later in Mexico. The exhibition drives this point home well with a selection of images that illuminate the photographer’s charge to find the perfect angle with which to capture what appeared in front of her lens.

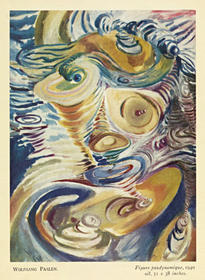

Less attended to in the exhibition is Paalen’s almost fanatical interest in developments in physics and wave theory, all of which filled the pages of various issues of Dyn. The final pairing in the main room does, however, shed light on Paalen’s application of scientific theory within his own artistic practice. Space Unbound (1941) is suspended above several issues of Dyn and a book by Erwin Schrödinger that contains illustrations of the scientist’s theories on wave mechanics. Paalen attended a lecture given by Schrödinger in 1927 in Vienna, and Space Unbound is meant to show Paalen’s debt to Schrödinger’s waves. Regardless of who or what motivated Paalen to paint Space Unbound, it is a fantastic, rhythmic painting with rings of color forming swirling tornadoes that dance across the picture plane. It is this work that best typifies Paalen’s practice in Europe and in Mexico. These pieces, in particular, were what attracted Lee Mullican to Paalen and to the Dyn group, and were a prominent feature of an exhibition organized by Paalen, Mullican, and Onslow Ford at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1951.

Because of the breadth of objects on display, Farewell to Surrealism opens up a wide range of questions and possibilities for thinking about the Dyn journal, the Dyn circle, Surrealism, artistic networks, and the transatlantic exchanges that occurred during World War II. Although separated from Europe by thousands of miles of land and water, Paalen was unable to completely extricate himself from his Surrealist background. Yet, in Mexico, away from Breton, he formed a new circle that drew upon Surrealist aesthetics while questioning new possibilities for art.

MacKenzie Stevens

PhD candidate, Department of Art History, University of Southern California