- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

When, in The London Quarterly Review of April 1857, Lady Elizabeth Eastlake wrote that photography’s “business is to give evidence of facts, as minutely and as impartially as, to our shame, only an unreasoning machine can give” (466), she voiced a widely held desire that photography would do two things: first, tell the truth; and second, liberate painting. Eastlake imagined photography’s contribution to art in terms of class, noting that, where once painting had dutifully devoted itself to verisimilitude, photography’s arrival had freed it from that responsibility. “The field of delineation,” she wrote, “having two distinct spheres, requires two distinct labourers; but though hitherto the freewoman has done the work of the bondwoman, there is no fear that the position should be in the future reversed” (466). Photography, in other words, was the new slave to faithful representation, while art, the “freewoman,” could finally do as she wished.

This view of photography as dutiful drudge to realism (there is “no fear” of its being art) seems to be the one that Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Mia Fineman sets out to challenge in her exhibition Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop. As a title, Faking It could probably reference just about any kind of representation, photographic or otherwise. Painted portraits aren’t people, words aren’t things, and photographs, for all that they are things, aren’t actually the things they depict. All representation involves a degree of fakery on the part of the maker, as well as a willing acquiescence on the part of the reader to be, as it were, faked out. What makes photography a particularly fertile ground for reflecting on the relationship between art and cheating, of course, is the camera’s supposed promise of truthfulness—but this promise was never made, even though we might wish it had been. Recall those early daguerreotypes of city streets, empty of human and animal life that moved too fast to be captured by the slow-moving process. Is this manipulation? No; but it is not exactly the truth, either. The most dependable truth of such images is what they tell us about photographic technology at the moment of their making.

This is an observation that might usefully be applied to any of the works in Faking It. Most obviously, they speak to photography’s technological limits and the desire to transcend them. But they also tell us about the historical moment at which they were made, as well as the viewing expectations of the persons for whom they were intended. The primary point of this exhibition seems to be that photography was never the bondwoman of Eastlake’s imagination, solely in service to the truth. Instead, the catalogue notes, “What will come as a revelation to readers . . . is that nearly every type of manipulation we associate with Adobe’s now-ubiquitous Photoshop software was also part of photography’s predigital repertoire. . . . The desire and determination to modify the camera image are as old as photography itself” (jacket).

Leaving aside the notion that it might be a “revelation” that photographic manipulation did not begin with the computer age (the plot of Thomas Hardy’s 1871 page-turner, Desperate Remedies, for example, was not the first to depend on trick photography), the exhibition itself implicitly defers to binaries—false/true, straight/trick, pre/postdigital—that, in some ways, its images counter. If these photographs are “faking it,” what are other photographs doing with “it”? Presenting it as it really is? Surely the degree to which a photograph represents—or manipulates—the truth about anything is always up for discussion. “One might argue,” as indeed Fineman herself does in the catalogue, “that there is no such thing as an absolutely unmanipulated photograph” (6; emphasis in original).

While the exhibition largely sidesteps or flattens out the more complex questions it raises about photography’s relationship to what is real, Fineman’s excellent and comprehensive catalogue addresses the most important one right away: “So, what do I mean by ‘manipulated’ photography?” The answer is deceptively simple: “the final image is not identical to what the camera ‘saw’ in the instant at which the negative was exposed. Some of the photographs were manipulated while the film was still in the camera . . . but the majority were altered in ‘postproduction,’ through techniques such as combination printing . . . photomontage, overpainting, and retouching the negative or the print.” The result of such intervention, Fineman adds, is that “the meaning and content of the original camera image have been significantly transformed by the process of manipulation” (7; emphasis in original).

It seems to this viewer, at least, that it is the intentionality of the transformation of content and meaning that lends each image interest. What is the story that we’re looking at? What purpose did each particular manipulation serve? During the two visits I paid to the exhibiton, it was interesting how many museum-goers appeared to be particularly drawn to those captions that addressed the intent of each photograph. In contextualizing the images, thus making visible the play with truthfulness that is not otherwise readily apparent, the captions, like the catalogue, are fascinating and necessary accomplices to the work of the photographs.

And there is plenty of intentional untruthfulness to consider. The many different kinds of photographs exhibited here were altered in a variety of ways for a variety of reasons, some aesthetic, some political, some merely the product of creative play with a camera. The photographs are arranged thematically and more or less chronologically, although at the outset, given the bottleneck of the gallery space, they must wrestle for our attention. In the cramped entry to the exhibition, no one wants to pause much at the first couple of images for fear of holding up the line. Further on, however, the space is more inviting, and larger areas allow for displays (books, a stereoscope) that provide a greater diversity of viewpoints, as well as a reminder of the many ways in which photographs are folded into lived experience.

In its earliest days, photographic manipulation sought to replicate what the human eye might see in the natural world—hence the hand-tinting of daguerreotypes, and the sketched and water-colored backgrounds of individual and family portraits. The purpose was to delight and charm the viewer, rather than to deceive or amaze. Likewise, combination printing was for the most part aesthetically motivated. Calvert Jones’s early calotype of monks on Malta (Capuchin Friars, 1846), a simple group portrait that called, the photographer apparently thought, for one of the monks to be removed from the print, is an obvious example of an intervention undertaken to secure the best “picture” rather than the most accurate document. Carleton Watkins’s stunning albumen print Cape Horn, Columbia River, Oregon (1867) benefits similarly from the photographer’s use of separate negatives for land and sky, so that the resulting picture has an arrangement of clouds that gives depth to the whole. Here the exhibition offers a kind of “before and after” effect through the display of two different versions of the print, one with and one without a clouded sky.

There are plenty of canonical images from photography’s pictorial history, including Robinson’s Fading Away (1858) and Rejlander’s The Two Ways of Life (1857). The notoriety of these two photographs arguably had to do as much with content as with manipulation, though each offended in different ways. Unlike Rejlander’s morality tale, Robinson’s picture contains no nudity, but to show the dying hours of a young girl was considered painful and problematic, a violation of the boundaries of good taste. Those boundaries were, interestingly, not restored by Robinson’s admission that the girl was, in fact, perfectly healthy and the photograph the product not just of multiple prints, but also of acting. Some viewers were offended by this news, too, and did not appreciate the fact that their emotional responses to the photograph had been manipulated.

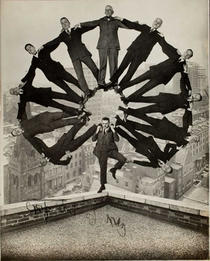

Odd as it seems to a contemporary viewer, when first exposed to photographs that, to the modern eye, were clearly put together with scissors, paste, and multiple negatives, Victorian readers were not always sure what they were witnessing. The “cobbled together construction,” as Fineman puts it (54), was initially confusing, especially in the case of crowd photographs made with several negatives or glued-together collages of photographed faces. The response to such scenes was, at times, bewilderment. How was it that the entire court of Napoleon III, as rendered by André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (ca. 1866), could be viewed all at once, seemingly from above, with no perspective? How could one moment in time have captured all the gentlemen of George Washington Wilson’s Aberdeen Portraits No. 1 (1857) together?

Faking It offers a number of reminders that vision is historically determined (the Cottingley Fairy photographs of 1917 are a wonderful example of this; surprisingly, they are not part of the exhibition). Ethical questions are, moreover, invariably present when time itself is the subject of manipulation, a point driven home by early photographs in which someone late to a group sitting is photographed and inserted into the image afterwards. In a more sinister reverse variation, some later group portraits show individuals who, although they were indeed photographed together, were subsequently removed from the picture in the service of grim politics. A Russian book on display, for example, shows Stalin flanked by four men at a party conference of 1926. Subsequent versions of the same photograph in later books show Stalin with three, then two, and finally, one companion.

What is interesting here, of course, is the history that gives context and meaning to the photographs and puts their manipulation in a more problematic light. Maybe it was the exhibition’s Washington setting, but the politically inspired interventions seemed, by far, the most compelling. Like the changes made to the photograph of Stalin, some are clearly designed not to be noticed: in a panorama made in Stalingrad, 1942, for example, a parade of downtrodden POWs is lengthened by the repetition of some of the figures, so that if you look closely, you can make out the same men appearing elsewhere in the line. Some changes are subtle, such as adjustments of the airbrush variety to enhance the appearance of political leaders (Chairman Mao, 1964); others are overt, creative, vicious in effect, and fabulous in conception, such as Barbara Morgan’s photograph of media scion William Randolph Hearst as an octopus-like cloud, his tentacles overshadowing the oblivious crowds below (Hearst over the People, 1939).

Photographs from later decades of the twentieth century reflect the changing emphases not just of politics, but of the arts, science, and philosophy. To chart the many places where photographers have been drawn to manipulate their images is, it turns out, to create a history of how we see, and of what we have wished, or been taught, to see differently. Faking It—best experienced in consultation with its catalogue—offers thought-provoking insight into photography’s role in shaping our complex relationship to the idea of the real.

Jennifer Green-Lewis

Associate Professor, Department of English, George Washington University