- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

The newly commissioned, site-specific installation, Figura que defina su propio horizonte (Figure Who Defines His Own Horizon), by the Cuban-born artist José Bedia is an apt centerpiece to his career survey, Transcultural Pilgrim: Three Decades of Work by José Bedia. A diminutive figure in dark bronze—a trickster as well as a reference to the artist himself, with a horned head and smoking a cigarette—is chained by the ankle to a tree stump. The chain and stump are a restraint, but in the context of Bedia’s idiosyncratic iconography, they are also an umbilical or tether that links the artist to specific places where he has grounded himself in local spiritual practices: his native Cuba, the Great Plains of North American, the desert of Northwestern Mexico and the American Southwest, and Central Africa. Holding a long pole that extends to the gallery wall, the bronze figure draws a horizon line. The horizon is a recurring motif in Bedia’s art—a symbol of travel and itinerancy—along with airplanes, boats, and other vessels in which one traverses borders, through which one connects with foreign cultures. In Figura que defina su propio horizonte, the horizon line folds over onto itself to form an open chevron. One arm, ending in an open hand—an imprint of the artist’s—reaches toward a model airplane, which maneuvers to avoid a volley of arrows as it slips beyond the vanishing point. The other arm of the horizon forms a clenched fist, landing a punch on the jaw of a looming profile bust—a massive mountain of black paint applied by hand to the gallery wall.

A fixture in the international art world since his inclusion in the innovative global exhibition Magiciens de la terre at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris in 1989, Bedia has traveled and worked extensively in far-flung locales. But his career has been distinguished from a cohort of similarly nomadic and itinerant “global” artists familiar from the contemporary biennial circuit, who produce sensational works for similarly rootless art audiences. Bedia’s counterexample exemplifies what Nicolas Bourriaud has described as “the radicant”—borrowing a term from botany, and describing plants such as ivy, which puts down new roots from the stem as it moves across the terrain (Nicolas Bourriaud, The Radicant, New York: Sternberg Press, 2009). Like a radicant, Bedia sets down roots as he travels, making a home for himself in the journey.

Transcultural Pilgrim was organized by two prodigious scholars well-suited to illuminate the rich, intercultural mix evident in Bedia’s art and life. Co-curators Judith Bettelheim and Janet Catherine Berlo are, respectively, experts in the arts of the African Diaspora—especially the Caribbean—and the indigenous Americas. The installation Figura que defina su propio horizonte is a catalog of themes of travel and emplacement that Bedia has pursued over his career. The exhibition highlights the artist as what Bettelheim and Berlo term a “transcultural pilgrim.” Since the 1980s, Bedia has produced paintings, drawings, and installations that mine an eclectic range of spiritual practices in an idiosyncratic visual style informed equally by vernacular art traditions and Neoexpressionist figuration current in the international art world when Bedia emerged as a young artist.

Art produced in the course of Bedia’s spiritual wanderings forms a predominant theme of Transcultural Pilgrim. Bettelheim and Berlo organized the exhibition into five sections—each focused on artworks produced in dialogue with Bedia’s transcultural journeys, including his investigations into the spiritual practices of the indigenous Americas (Bedia is an initiate in Cuban Palo Monte and the Native American peyote cult—syncretic traditions that meld Christianity with indigenous religion), and time spent in the Peruvian Amazon and Zambia, where he studied with shamans and other spiritual teachers. A final section includes artworks paying homage to Cuban revolutionaries whose religious devotion underlay their social and political mission.

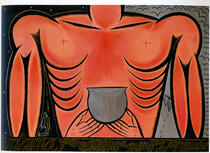

All these practices to some extent focus on sacred power objects and spiritual animals or personages, including the shape-shifting trickster. Along with emblems of travel, they also become recurring motifs in Bedia’s personal iconography. A signature work for the exhibition is Mama quiere menga, menga de su nkombo (Mama Wants Blood, Blood of His Bull), a 1988 self-portrait of Bedia as Palo Monte initiate, his torso and hands shown with ritual scratch marks and presenting to the viewer an empty nganga or ritual vessel, ready to be filled. The painting also contains iconography denoting transit and transition, a car traveling along a dark roadway, a lone figure walking leaving a trail of footprints, a starry night sky, and a contrasting daytime sky filled with forms suggesting clouds or flock of migrating birds. Bedia’s iconography—the initiate, the ritual vessel, the path or trail, the solitary pilgrim, birds in flight—suggests movement and personal transformation, recurring themes that recount his experiences in Cuba, Africa, or the Americas.

One particularly moving, if understated, strategy is displayed in several large (96.5 × 127 cm) exhibited works on paper. For these monochrome pieces, Bedia affixes a black-and-white reproduction of a historic photograph—for example, an anthropologist’s image of a sweat lodge or peyote ceremony, or a nineteenth-century Afro-Cuban political leader—around and in response to which Bedia renders a ghostly, expressionistic figure or group in oil stick, charcoal, or pencil. Bedia’s characteristic elongated forms are like shadows cast by the past, as the artist plumbs the archive for inspiration.

In addition to highlighting Bedia’s catholic spiritual interests, Bettelheim and Berlo included in the Fowler exhibition several ancillary installations—curated selections from Bedia’s own extensive collection of ethnographic artworks. These include a Palo Monte altar, fetish objects from Africa, masks from Mexico, and ledger drawings and peyote boxes from North America. These installations provided a counterpoint to Bedia’s paintings and drawings, as well as giving some insight into the ways in which Bedia lives with artworks made by his tribal acquaintances.

In conjunction with his retrospective at the Fowler, a museum specializing in ethnographic arts, Bedia was invited to curate a concurrent exhibition from the museum’s permanent collection. Bedia Selects brought to light a group of more than thirty Central African objects that had never been previously exhibited. With a focus on unusual utilitarian wares and ritual artworks, including stunning Tutsi dance shields painted in geometric patterns and a very rare Sala Mpasu dance platform, Bedia’s exhibition-within-an-exhibition also revealed the breadth and depth of the artist’s interests and affinities. It was refreshing to see such fascinating artworks and artifacts selected with an artist’s eye to formal beauty, as well as with attention to their spiritual power and import.

Bettelheim and Berlo describe Bedia as a “citizen of multiple art worlds.” The artist’s connections have not been only with other biennial artists and celebrity curators, but with vernacular artists and indigenous spiritual practitioners. In the exhibition and in the excellent catalogue, a profile emerges of Bedia as what Bettelheim and Berlo term a “vernacular cosmopolitan.” Bedia interacts with and borrows from tribal artists as his contemporaries, often as his guides and teachers. His art practice (like his spiritual practice) is intercultural and inter-hemispheric—invoking the syncretism of the Atlantic world as formed by colonial patterns of triangular trade between Europe, Africa, and the Americas in natural resources and human slaves, and as reconfigured by the politics of the Cold War (Bedia’s first trip to Africa was as a draftee in the Cuban army deployed to Angola). To be sure, Bedia is not a romantic primitivist; Bettelheim and Berlo are clear to distinguish his explorations of shamanism from those of Joseph Beuys, Lothar Baumgarten, and other artists who appropriated indigenous spiritual practices as a foil for Western modernity. Viewing the extensive bodies of work Bedia has produced in the Caribbean, Africa, and the Americas, one gets the sense that Bedia’s art provides a powerful model of the artist not just as anthropologist, but as spiritual striver and earnest champion of cultural mixing at every level.

Transcultural Pilgrim was also the most recent of the Fowler’s efforts to erase distinctions between “traditional” or “tribal” arts and the “modern” and “contemporary” art that comprises much of mainstream museum programming, international biennials, and art fairs. As Bedia reminds his viewers, the makers of the beautiful and exotic artworks in ethnographic museum collections were also moderns, formed by the legacies of colonialism and navigating global world systems. In other words, living tribal artists are also inhabitants of the contemporary milieu. Recent exhibitions at the Fowler by contemporary artists, including Nick Cave and Allan de Souza, and showcasing contemporary phenomena such as the Chicano art movement of the 1970s, street art, and ongoing practices such as ceramics and weaving, have gone a long way toward recognizing the multiple temporalities and cultural fusions of the global present. In this context, Bedia is right at home again.

Bill Anthes

Associate Professor of Art History, Pitzer College