- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Two recent exhibitions, one in Boston and the other in New York City, highlighted the central role that printmaking has played in South African art for the past half century and provided an exciting introduction to its varied achievements. In South Africa, where art has frequently served as a vehicle for protesting political oppression, printmaking has been valued for producing multiples that can be widely disseminated by resistance organizations. In addition, in a country where the majority of the population has until recently been provided with a “bantu” education, certain processes, such as linocut, have provided an inexpensive vehicle for community-based art instruction. And finally, because of its close connection to political and social concerns, printmaking has been central to the artistic production of many of South Africa’s most prominent fine artists. One benefit of these two museum surveys is to have introduced the public to a number of outstanding artists who have not been seen previously in the United States. (One could think of the exhibitions as “Kentridge in context,” and in fact Kentridge did deliver a brilliant lecture on his current research into theories of time as part of Boston University’s accompanying programming.) In addition, Judith Hecker, Assistant Curator, Department of Prints and Illustrated Books at the Museum of Modern Art, previously worked directly with Kentridge on Trace: Prints from the Museum of Modern Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), which was published at the time of the artist’s MoMA retrospective, and is not just a compendium, but is in effect an artist’s book.

Boston University hosted an ambitious two-part exhibition that presented a wide-ranging survey of the first independent printmaking studio in South Africa, the Caversham Press, founded in 1985 by artist Malcolm Christian in the rural Balgowan valley in KwaZulu-Natal. South Africa: Artists, Prints, Community: Twenty-five Years at the Caversham Press, included 120 prints by 70 artists, whereas Three Artists at the Caversham Press: Deborah Bell, Robert Hodgins and William Kentridge was a more focused look at three prominent artists who were among the first to work together at the press in the 1980s and 1990s. Both parts of the exhibition were curated by Lynne Cooney, Director of Exhibitions at Boston University’s School of Visual Arts.

Impressions from South Africa: 1965 to Now, curated by Hecker, in large part from the collection that she assembled for the museum over several visits to South Africa, was smaller and more tightly organized, and in the context of MoMA’s own exhibition and collecting histories, constituted a departure for that institution.

To begin with Boston University’s exhibition, South Africa: Artists, Prints, Community: Twenty-five Years at the Caversham Press, as installed in the university’s cavernous 808 Gallery, was organized according to its various programs: the Caversham Press Educational Trust (1993– ), the Hourglass Residency Program (1998– ), the Caversham Centre for Artists and Writers (2000– ), and the CreACTive outreach centres (2003). The first wall seduced the viewer into this unfamiliar territory by highlighting university-trained artists who came to Caversham to do personal work with the assistance of Christian’s exceptional technical skills. As such, these artists, including Andrew Verster, Malcolm Payne, and Bronwen Findlay, exemplify the press’s vision statement: “inspiration in the individual and the individual as inspiration.” It required no small amount of inspiration to purchase an abandoned Wesleyan Methodist church and to establish a printmaking studio in 1985, during the height of the state of emergency with its accompanying rampant violence. Yet, Caversham was and remains a quiet retreat supporting the vision of each artist who comes to work in the studio, whether from distant cities or from surrounding communities. In 1993, no doubt in response to the new democracy to be established the following year, Christian established the Caversham Press Educational Trust as a nonprofit in order to provide ongoing workshops for emergent black artists. As he notes in his interview with Elza Miles, “Caversham: Where Visions Are Allowed to Grow,” “After the devastation of apartheid, a deep need remains to re-grow connections, reconnecting the continuity of legacy through mentorship between vitality of youth and life-wisdom of elders” (95). According to the gallery label, over 250 artists have had skills development training to date, an impressive number. In this regard, the Trust has built on the legacy of the ELC Art and Craft Centre in Rorke’s Drift KZN (1963–1982), where many of South Africa’s most outstanding black artists had been trained. (The Rorke’s Drift artists were highlighted in Impressions from South Africa: 1965 to Now at MoMA.) Although there were only tentative links with Caversham, as Rorke’s Drift had closed three years before Caversham was founded, the press has arguably “followed the valuable work achieved decades earlier . . . in offering facilities, skills-based knowledge, and empowerment through visual expression” (8). For example, the theme of the first workshop, “The Spirit of Our Stories,” has provided ongoing inspiration for Sthembiso Sibisi, whose colorful linocuts of township life in Kwa-Zulu Natal display a virtuoso draftsmanship that Christian pointed to with pride in his gallery talks.

To permit the expanding number of South African artists working at Caversham to be included in the development of contemporary printmaking internationally, Christian established the Hourglass Residency Program, and in 1999 the portfolio “A Women’s Vision” traveled to the Fulton County Arts Council in Atlanta, leading to a formal partnership with that organization. One of the fifteen participants from five countries in this first exchange was Lynne Allen, current director of Boston University’s School of Visual Arts. Allen’s witty and dazzling print, My Winter Count, (1999) was included in the exhibition, but neither the label for the work nor the wall text indicated the central role she played in serving as the conduit between Boston University and Caversham; this information can only be gleaned by reading her “Forward” in the catalogue. In addition to the interview with Christian, the catalogue includes a total of seven individual testimonials to the experience of working at Caversham. As a result, the tone of the catalogue’s design and content, with its transparent overlays and emphasis on the artist’s voice as expressed through personal reminiscences, is one of a retrospective rather than an anniversary celebration. In both the exhibition and the catalogue, the stress on the individual and the commitment to printmaking as a democratic medium produces an almost self-contradictory result: there is no biographical information provided for any of the artists, either on the labels or in the catalogue.

The one artist who provides a stable core for this otherwise diffuse survey is Gabisile Nkosi. According to the catalogue’s indispensible history by art historian Marion Arnold, “Sawubona Caversham: Home of People and Prints,” Nkosi joined the press in 2002 as the first (training) program manager and community coordinator. The following year, she organized the CreACTive centres in the nearby rural towns (14–15). The seventeen brilliant linocuts by Nkosi included here constituted a sort of a mini-retrospective. Among the themes depicted are her difficulties with her violent partner (who eventually murdered her) as well as the sheltering and stimulating environment offered at Caversham. Her monumental Journey of Inspiration (2004), reproduced on the catalogue’s cover, is a moving visual testimony to the efficacy of Caversham’s philosophy of empowerment through the nurturing of artistic talent. Sadly, Nkosi is but one example of the many emerging talents lost to violence and HIV/AIDS over the past twenty-five years. When Nkosi died, Christian’s vision for a Caversham Press eventually run by black artists and administrators was diminished, although the three young administrators who came to Boston with Christian and who participated in his walkthroughs are clearly dedicated to the organization’s work.

The second part of the exhibition—the work of three prominent white South Africans who made prints together at Caversham in its early years—brought the viewer back to Caversham’s origins as an atelier for established artists. Seeing the prints of Deborah Bell, Robert Hodgins, and William Kentridge together in the same space made it evident that for this group of artist friends collaboration meant working side by side and sharing ideas, while developing their own approaches to the topics of “Hogarth in Johannesburg” (1986), “Little Morals” (1991) and “Ubu Tells the Truth” (1996). The catalogue essay by Boston University graduate student S. J. Brooks, “The Early Years of the Caversham Press: Three Portfolios,” quotes Bell as stating that, “I allowed myself to be absorbed and influenced . . . to steal imagery and to have imagery ‘stolen’ in return” (43). A clear example of this “theft” is the influence of the elder Hodgins on Kentridge. Apparently, it was Hodgins who first began working on the Ubu theme that led to Kentridge’s prints and sets for Ubu and the Truth Commission (1997). And the pinstriped, rapacious businessman and amoral military officer, two icons Hodgins borrowed in turn from German expressionists such as George Grosz, have become staples of Kentridge’s iconography. Both the Boston University and the MoMA exhibitions present the visual evidence for this seminal influence, but do not elaborate on it. In any event, the fact that this exhibition within a retrospective was separated out from the larger survey suggests that at heart Christian is dedicated to the fine art print, a beautifully made studio product by an individual artist, regardless of its possible social or political ramifications.

In contrast to Boston University’s broad, retrospective survey, MoMA’s Impressions from South Africa: 1965 to Now was dense with focused content. Works by twenty-five artists and five activist organizations were organized by medium, which also served as a rough chronology and registered the artists’ varying responses to pressing political issues both pre- and post-apartheid. From the point of view of the exhibition’s audience, the exhibition made no claim to being comprehensive; rather each work and each section was part of a clear, comprehensible overview. Hecker’s catalogue essay is as concisely and lucidly organized as the exhibition itself, and in summarizing sources that may not be readily available to a Western audience, provides as solid an introduction to South African printmaking as one could hope for. The key to the exhibition’s importance, however, was in its subtitle: Prints from the Museum of Modern Art. Because of Hecker’s diligence, the museum has been out front in purchasing works by South African artists without an international reputation. As she points out in her introductory essay, “Impressions from South Africa, 1965 to Now”:

Of course the works cannot speak for the entirety of a medium within a country over a period of time; the collection was assembled with the goal of conveying the unusual reach, range, and impact of printmaking in South Africa while also introducing new artists to the Museum’s collection. These works dispense with notions of classification that distinguish between contemporary and traditional, fine art and craft, high and low art, the art world and community arts; instead, they take a broad-ranging and inclusive definition of contemporary art. At the same time, individual works emphasize that not all art has been created equally in South Africa—that not all artists have had the same opportunities. (12)

In sum, the exhibition shared with Caversham the premise that the separate and incredibly unequal situations in which South African printmakers have worked have nonetheless generated creative interchanges that serve to broaden a view of what constitutes contemporary art.

The catalogue essay begins with the linocut, the inexpensive medium that was and continues to be widely used in community arts centers to train disadvantaged black artists. As mentioned previously, the ELC Art and Craft Center in Rorke’s Drift, founded in 1962, was one of the most influential of these centers, and its influence reverberates throughout South African printmaking today, as the exhibition demonstrated. The date of 1965 that begins the survey is the date of the first print by a South African artist to enter the MoMA’s collection: The woman who loved and was / Innocent from accusation, by Azaria Mbatha, who was trained and taught at Rorke’s Drift. What was once a lone outlier in the museum’s print collection now has a true home.

However, the exhibition itself did not begin with this historical precedent. Instead, in the first gallery Hecker elected to juxtapose two prints of military thugs by Kentridge and Hodgins with a wall of ephemeral posters and stickers, the majority screen-printed, that were produced, often under the threat of violent reprisal, to agitate against the apartheid regime. Included are classics such as Judy Seidman’s You Strike the Woman (1981), which was also part of the retrospective, Thami Mynele + the Medu Art Ensemble, at the Johannesburg Art Gallery in 2009. At MoMA, the wall of posters and stickers produced by cultural workers working in collaboration with or under the aegis of larger groups such as the United Democratic Front or the Congress of South African Trade Unions was riveting, especially in its collage-like installation. Although the specific imagery of banners or raised fists was predictable, the compositions were nonetheless powerful. In this instance, the “democratic” medium had had a direct role in helping to bring about democracy. Obtaining the works of prominent fine art resistance art artists such as Kentridge, Sue Williamson, and Norman Catherine, who are also part of the exhibition, was a relatively straightforward task; sourcing these ephemeral posters so many years after they were created was a real achievement, especially as they are now part of the permanent collection. This fact is especially impressive to me as a Bostonian, as the Museum of Fine Arts’s collection of prints from South Africa consists only of work by white artists.

The exhibition also demonstrated that the commitment to political commentary and agitation did not end with the first democratic election in 1994. The Durban-based Art for Humanity’s “Break the Silence” HIV/AIDS billboard campaign (2000–01) was included, as was Diane Victor’s harrowing “Disasters of Peace” series of etchings (2001–present), which, as Hecker writes, “call attention to . . . the everyday disasters that are apartheid’s legacy” (26). The etching of an infant who had been gang-raped in order to “cure” the rapists of HIV planted itself indelibly in the mind. In addition, Hecker stretched the definition of printmaking to include the mordant and often perverse humor of Bitterkomix, the underground graphic comic founded by Anton Kannemeyer and Conrad Botes in 1992. In the final gallery, Hecker included contemporary examples of linocut, displaying works as disparate as Senzeni Marasala’s moving “Theodorah” series (2005), based on memories of her mother, a domestic worker, and Paul Edmunds’s stunning six-foot-high linocut of a single, unbroken line creating a thumb-print “self-portrait” as it threads down the surface.

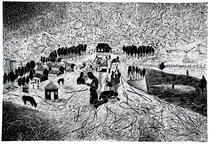

The most provocative example of contemporary linocut was in fact not a print at all but a drawing by Durban-based Cameron Platter. The large-scale The Battle of Rorke’s Drift at Club Dirty Den (2009) appropriates the style and subject matter of John Muafangejo’s famous linocut, The Battle of Rorke’s Drift (1981), to reference through its spear-bearing dancers the violence and debauchery of much of contemporary, quotidian South African life. What at first appeared to be a puerile appropriation by a white artist of one of the iconic works of South African art history became in this context a continuation of the political commentary on the failed ideals of the “new” South Africa, in a manner comparable to Victor’s “Disasters of Peace.” His technical skill in creating the illusion of a linocut in black-colored pencil is also comparable to Victor’s in its breathtaking virtuosity.

Upon leaving the exhibition, one encountered the powerful posters and graffiti works of Zimbabwean artist Kudzanai Chiurai; the two graffiti works were in fact spraypainted on the gallery’s exterior walls. (Because he was unable to come to the United States due to passport issues, Chiurai sent over the stencils he uses for his graffiti, and the work was executed by MoMA’s head painter.) The helmeted military thugs so familiar from resistance art live on, as representative now of the political corruption and violence that has destroyed the civic life of South Africa’s nearest neighbor. Chiurai’s imposing spray paintings can be found on public walls around Johannesburg, bearing witness to the same faith in the ability of art to bring about social change that motivated the cultural workers of the 1980s, and bringing South Africa’s activist art history into the present.

The end matter of the catalogue for Impressions from South Africa: 1965 to Now contains an invaluable compendium of information that will provide a major resource for scholars in the future. Included in these “yellow pages” are an extensive chronology (1948 to the present), artist biographies, notes on artists and political organizations, notes on publishers and printers (printmaking studios), and a selected bibliography. Although MoMA has exhibited political prints in the past, Impressions from South Africa: 1965 to Now asked viewers to confront the current relationship between art and politics. I see it as a deceptively modest tugboat gently guiding the ocean liner that is MoMA in a new direction.

Pamela Allara

Visiting Researcher, African Studies Center, Boston University