- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

The current, straightforwardly titled Frida Kahlo retrospective, organized by the Walker Art Center and traveling to Philadelphia and San Francisco, follows two unrelated but identically titled surveys of the same artist—one organized by the Tate Modern (2005) and another, more hastily put together, at the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City (2007), each with unique, well-illustrated catalogues. While the shows in Mexico and the United States were explicitly tied to the centennial of Kahlo’s 1907 birth, the Tate version seems to have been conceptualized as the best way to get British audiences excited about Latin American art, a new curatorial direction for the museum. Kahlo, after all, is the number one crowd-pleaser as far as Latin American art is concerned—like Van Gogh and O’Keeffe, one can count on her to sell tickets.

Great Kahlos are now worth several million dollars: they might be a bargain in comparison with some of her European contemporaries but are at the pinnacle of the Latin American market. These shows are thus expensive organizational nightmares, requiring diplomatic negotiations with collectors and institutions increasingly reticent to lend their over-requested works. But judging by popular success, the varied efforts were all well worth it, even if the lines in London and Philadelphia paled in comparison to those in Mexico City, where some people waited eight hours in the sun on closing day before entering the jammed galleries of the Palacio de Bellas Artes. Crowded exhibitions are now all too common, but it was a bit unsettling in Philadelphia to see so many people leaning in toward Kahlo’s diminutive Henry Ford Hospital (1932), peering at her crotch in a communal act of voyeurism that resonated with the nearby installation of Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés.

In terms of the checklist, the current Frida Kahlo show is a tight, well-edited survey that includes many of her greatest pictures, including The Two Fridas (1939), one of her largest paintings and the only major Kahlo in Mexico’s national collections. The installation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) was clean, with the widely spaced and brightly lit pictures set against dark red and green walls that gave a Mexicanist treasure-chamber effect: the only annoying element was the tacky gilt frames that uniformly surround the works lent by the Dolores Olmedo Museum in Mexico City, but there was nothing that could have been done to remove them. There were some notable absences, some the result of denied loans, like My Birth (1932), owned by none other than Madonna. Others resulted from particular curatorial decisions: for example, the show included only one work from the 1920s, Kahlo’s first self-portrait (which did not travel to Philadelphia), though the years before her marriage to Diego Rivera were a time of interesting visual experiments. At the same time, the curators smartly omitted most of the minor works that Kahlo fans treasure like so many saintly relics—the illustrated letters from her schoolgirl days, the weird ink drawings, and especially (thankfully) the terrible late pictures marred by the shaking hand of an artist sadly addicted to painkillers.

In the end, it was hard for specialists in the field of Latin American art to get very emotional about the show one way or another. It was perfectly workmanlike, yet offered almost nothing fresh except the chance to see some previously unpublished photographs of the artist as well as a couple of rarely exhibited works from private collections like The Dream (1940) and Magnolias (1945), rendered with wax-like petals that practically reeked of the heavy sweetness of the actual flowers. Actually most of Kahlo’s famous images are easily visited by dedicated pilgrims, whether in the Olmedo Museum or the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, housed in a new museum in Cuernavaca since 2004—these two institutions alone hold over two dozen key pictures—or in the other public museums with Kahlo paintings, which almost always have these popular attractions on public display.

Not only were there few little-known works on display in this exhibition, there were few new facts, either. Indeed, neither the Walker show nor the previous retrospectives in London and Mexico City reflected groundbreaking discoveries or revisionist methodologies. Of course, none could have taken advantage of the wealth of documents from her personal archive. These are only now being made available to researchers after being locked up for years in the Casa Azul—her family home converted into a house museum—despite the fact that Diego Rivera’s will ordered that these materials be open to scholars twenty-five years after his death, which occurred in 1957. There were also no revelations on the order of the discovery by German historians Gaby Franger and Rainer Huhle (in a biography of Wilhelm Kahlo) that Frida apparently faked her background, claiming that her father was Jewish in order to create an alter-ego in the mid-1930s that would identify her with the oppressed rather than the oppressor. For a good overview of the problem of Kahlo’s Jewishness, see Menachem Wecker’s “The Un-Chosen Artist” in The Jewish Press (September 25, 2007; consulted online at www.jewishpress.com). That disclosure undermined the work of several scholars, while reminding others of how perfectly Kahlo emblematizes the construction of personal identity, and of her continuing power to surprise us, just when we thought we knew everything there was to know.

There have been a few excellent reviews of the current Frida Kahlo show, particularly Sanford Schwartz’s balanced “The Nerve of Frida Kahlo” in the New York Review of Books (May 15, 2008) and Peter Schjeldahl’s gushing “All Souls” in The New Yorker (November 5, 2007), but two points bear further emphasis here. One concerns the narrow biographical approach taken by the curators, while the other relates to the broader role played by Fridamania in the ongoing construction of Latin American art history.

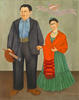

All shows require a narrative, but the major conceptual problem with this particular Frida Kahlo is that it unrelentingly situates her work in relation to biography, in both the installation and the wall labels. The second painting that viewers encountered at the PMA was her Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931), a fair way of saying that her career really began only after her marriage, which was followed by anterooms dedicated to a large collection of vintage photographs. (Viewing them may have tired some visitors before they got to the actual paintings.) Documents are to be expected in any retrospective, but here they were the required prologue, as if what was to follow couldn’t be understood without recourse to Kahlo’s personal life. The labels in the show confirmed this approach, generally leading off with some reference to sexual betrayal or bodily pain. None of this was surprising given that the exhibition was guest-curated by Hayden Herrera (together with Elizabeth Carpenter of the Walker), author of the 1983 biography of the artist that was so comprehensive and engaging that it still remains—twenty-five years out, and despite a few necessary corrections—the single best book on Kahlo. But the biographical approach that Herrera has taken for the past quarter century now seems more than just a bit tired, for it simply confirms what the general public has come to expect: Kahlo as illustrator rather than inventor.

Admittedly, the installation in Philadelphia did provide some non-biographical points of comparison. One wall allowed viewers to relate her small-format paintings, like Henry Ford Hospital, to the small Mexican ex-votos that commemorate divine salvation from catastrophe, while a small case of pre-Columbian art in the final gallery included a Teotihuacan mask not unlike the one worn by the indigenous figure in My Nurse and I (1937). The PMA also complemented the Kahlo show with two parallel exhibits located in nearby, but not adjacent, galleries: one, curated by Edward Sullivan, featured the early work of Mexican painter Juan Soriano; the other included most of the modern Mexican paintings in the PMA’s collection (probably second only to MoMA’s in terms of those formed in the 1930s and 1940s). All of this was designed to give the public a better idea of Kahlo’s aesthetic “world,” but to what extent general viewers were able to weave together all these implicit connections remains unclear. Thus, as in Kahlo’s house museum in Coyoacán, snapshots and local Mexican images served to inform her work, while other more international sources—from Mannerism to Surrealism—were safely relegated to illustrations in the catalogue.

For some within the field of Latin American art history, all of these criticisms are beside the point, for revising the checklist or reworking the catalogue would not change the fact that any Kahlo show, by its very nature, is a sort of Molotov cocktail of popular success mixed with an emphasis on Mexico and “fantastic” imagery. In other words, it is not only that the biographical approach reinforces stereotypes about Kahlo, but that the emphasis on Kahlo herself reinforces the centrality of Mexican modernism in narratives of Latin American art, just as her paintings reinforce preconceptions about Latin American art in general as figurative, earthy, tropical, emotional, identity-obsessed, and downright “other.” Mari Carmen Ramírez, Wortham Curator of Latin American Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and one of the leading forces in the field, recently placed the popular enthusiasm for Kahlo’s work in this very context: “My objection to Frida Kahlo is the phenomenon of Frida Kahlo and the way it obscures Latin American art. She was a woman with an exceptional capacity to present her own suffering through an amazing and rather unique style. But she didn’t have many followers. You can’t use her as an emblem for an entire continent. It’s absurd. . . . And of course, she wasn’t such a great painter either” (quoted in Arthur Lubow, “After Frida,” The New York Times Magazine [March 23, 2008]).

The questions of whether Kahlo had followers (she certainly did have an impact on Mexican and Chicano practice in the 1980s and 1990s, as Herrera discusses in the Frida Kahlo catalogue) or was a “great” painter are not really the issues of course. But however hyperbolic, this critique from within the field—which has been echoed by others in Mexico as well as in the United States—does merit further exploration. In part, it results from an understandable sense of exhaustion, not only with the monographs that go over the same material again and again, but also with the t-shirts, perfumes, barrio murals, movies, and even Madonna’s current “Super Pop,” where she chants, “If I was a painter, I’d be Frida Kahlo.”

But this Kahlo-bashing is also part of a necessary and ongoing corrective in which institutional biases in the United States that have long favored Mexican pre-war figuration—a result not only of geographic proximity but of the continual movement of artists across the Rio Grande—are challenged by relatively overshadowed figures and movements, mainly from post-war Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela, that remind us of the diverse strands of practice in Latin American art history. This, of course, was the program outlined by Ramírez’s revisionist exhibition Inverted Utopias (2004), and by the collection she has been building at Houston since moving there in 2001. Within this broader project, Kahlo is like the wrench in the machine, since no other Latin American artist will probably ever have such an irresistible hold on the U.S. public as Kahlo does.

At the same time, there is surely something to be redeemed about Kahlo, something beyond the uncritical popular embrace and the overly critical attacks. Kahlo’s messy art—erotic yet bloody, overheated, filled with chattering monkeys and pre-Columbian relics, to say nothing of the references to miscarriage, lesbian eroticism, and Stalinism, marked by great triumphs as well as terrible failures—reminds us that the world (and not just Latin America) is indeed itself a messy place, despite repeated efforts to impose political or aesthetic order. Kahlo’s best work forces us to unpack all sorts of vital issues, from racial blending and historical traumas to class identity and political oppression, all of which challenge us emotionally in ways that formalist and utopian abstractions can not. Surely the problem of the current exhibition is not that Kahlo is messy, but that it doesn’t draw all of her messiness out nearly enough.

More than “after Kahlo,” one might expect the pendulum will ultimately settle in some territory called “along with Kahlo,” that is inclusive rather than exclusionary. Sure, we in the field are all a bit tired of her face, we joke about the unibrow and relish the grotesque fakes that now circulate in the market, but even the broader public might not need another Frida extravaganza again for a while. Yet of all the artists of the twentieth century, Kahlo is one of the very few who created work that is absolutely unmistakable, and she won’t be going away anytime soon. Indeed, her constant stare might be there to remind us that she, perhaps more than any other artist, helped spark the shift in focus—by institutions, collectors, scholars, and the public—that has triggered contemporary interest in the U.S. and Europe in Latin American art, whether figurative or abstract, or from north or south of the equator. Someone had to get people to pay attention—in the end, all of us are to some extent the beneficiaries of Fridamania.

James Oles

Senior Lecturer, Art Department, Wellesley College